February is Black History Month, a time to recognize the achievement of local African American heroes and heroines. We invite the public to celebrate by visiting one of the many parks named for Seattle’s African American leaders, and to learn about their contributions to the city.

Part 1 of this series here.

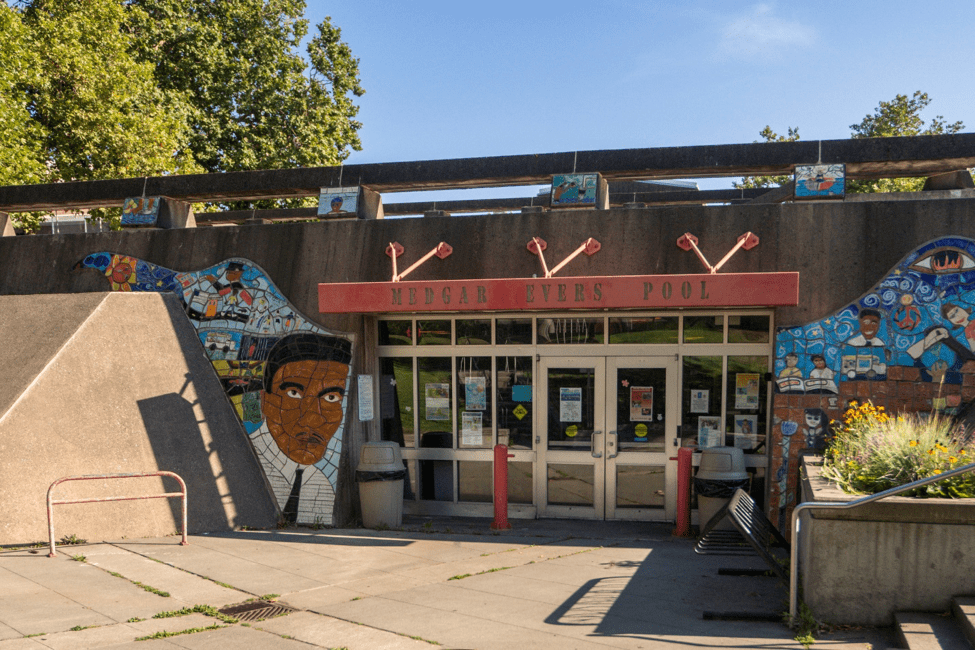

Medgar Evers Pool

Medgar Evers Pool is an indoor pool facility located on 23rd Ave., next to Garfield Community Center

Medgar Evers was a prominent civil rights leader. After serving in the U.S. Army and graduating from Alcorn State University, he moved to Mississippi and became involved with the Regional Council of Negro Leadership (RCNL). There he gained experience as an activist. He led multiple boycotts in protest of racist policies held by gas stations and retail stores.

In 1954, Evers applied to attend the University of Mississippi Law School, but was refused admission. As a result, the NAACP began campaigning to desegregate the school, leading to Evers becoming their first field officer in Mississippi. In that role, he investigated hate crimes against black people and supported the voter-registration movement. Though it took until 1962, Evers was key in the ultimate desegregation of the University of Mississippi.

In 1963, Medgar Evers was killed by a white supremacist. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors. Outrage over his tragic death fueled support for the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Today, his home in Jackson, Mississippi is under consideration to become a national monument.

John C. Little, Sr. Park

John C. Little, Sr. park is located in the NewHolly neighborhood. The park includes picnic shelters, a plaza, a children’s play area, and a community garden.

John C. Little, Sr.’s motto was, “In order to improve the life of all people, you must improve the life of young people.” In his lifetime, he received countless awards for community service and served as a member of the Washington Human Rights Commission and the Seattle Board of Park Commissioners.

In the 1960s, he helped to create the Central Area Youth Association, which provided youth athletic leagues, one-on-one tutoring, and job training. During the early 1970s, he helped devise a youth conservation corps in which urban youth trained and worked in Olympic National Park.

His legacy lives on at Seattle Parks and Recreation. An annual award in his honor recognizes the employee who exemplifies his service to youth and community.

William Grose Park

Located at 30th Ave. E and Howell St., this quiet neighborhood park features a rolling green lawn with giant evergreen along a short path.

Grose (1835-1898) was an African American pioneer. In 1876, Grose opened a restaurant and hotel on Yesler Way called “Our House.” Six years later, he bought 12 acres along E Madison St. from Henry Yesler, which became the foundation of the Central District. Grose was one of the founders of the First African Methodist Episcopal church in Seattle and was one of the wealthiest men in the city during his time. He was known as a generous neighbor who regularly helped those in need.

Prentis I. Frazier Park

Prentis I. Frazier Park (401 24th Ave. E) is a neighborhood park ideal for resting in the shade and playing. The park includes a small play area with benches. Construction began earlier this year on a renovation to the children’s play area.

The park is located behind the historic home of Prentis Frazier, who lived in Seattle in the early to mid-1900s. He was a skilled businessman, working in investments and real estate, and was committed to supporting black entrepreneurship in Seattle. In 1925, he and a partner opened a movie theater on E Madison St. Shortly thereafter, he started the Seattle Enterprise, a newspaper designed to serve black Seattleites. The paper continued to run until the 1950s. He lived in the Central District from the time he moved to Seattle until his death in 1959.

Alvin Larkins Park

Alvin Larkins Park, located at the corner of E Pike St. and 34th Ave. E, is a popular neighborhood gathering place for the Madrona community and frequently sees visitors strolling through from the nearby business district. It is landscaped with maple, pine, fir, and cherry trees. Seattle Parks and Recreation bought the land for the park in 1973 and developed it in 1975. In 1979, it was named Alvin Larkins Park based on the recommendation of the Madrona Community Council.

Al Larkins was a brilliant musician and teacher. While stationed at Sand Point Naval Air Station, he played in both the U.S. Naval Military Band and the Jive Bombers jazz band. He went on to graduate from the University of Washington and became a teacher with Seattle Public Schools, where he was an outstanding music instructor for many years. Larkins helped to found the Rainy City Jazz Band, which performed at the first Bumbershoot Festival, and played with Duke Ellington when he performed in Seattle. Larkins also directed the Madrona Presbyterian Church choir. He was a regular at neighborhood events, devoting time and energy to the Madrona community, where he lived from 1949 until his death in 1977.

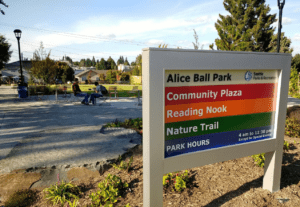

Alice Ball Park

Alice Ball Park opened in June 2019. The neighborhood park provides wonderful open space and community connections in the Greenwood neighborhood. The park features a multi-use space that includes natural play elements, an open lawn, a gathering/plaza space with seating, a loop path, and planted areas. The project also includes low-impact design strategies featuring amended soils, porous concrete, and increased infiltration created by the new open space.

The park is named after Alice Ball, an African American chemist who developed an injectable oil extract that was the most effective treatment for leprosy in the early 1900s. Born in Seattle in 1892, Ball graduated from the University of Washington in 1915 and became the first woman, and African American, to graduate with a master’s degree from the University of Hawaii.

————

See Part 1 of this series here.